Roads Pointed to Gettysburg: The Union Advance Through the Heart of Maryland

Running through the center of Maryland is hallowed ground – a term drawn from President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address – where thousands of Civil War soldiers spilled blood, thus rendering it sacred.

Today, the Maryland Journey Through Hallowed Ground Scenic Byway follows the footsteps of soldiers who marched through fields and towns on their way to battles that, for many, were their last. Visiting sites that stood witness to this bravery is a meaningful way to connect with the conflict whose repercussions we still feel today.

I grew up exploring the Gettysburg battlefield with my father, a Civil War buff who passed his love of history to me. While I knew that the troops advanced to and retreated from this pivotal battle through Maryland, I wanted to learn more. I was aided in this quest by Civil War Trails, a network of Civil War signage that created my itinerary for the day. Armed with my trusty Civil War Trails map, I hopped in my car and headed out.

The Lead Up to the Battle of Gettysburg

In June 1863, nine months after catastrophic casualties at Maryland’s Battle of Antietam, the Civil War was still raging. Confederate General Robert E. Lee was coming off a triumphant defeat of the Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville, VA. He felt the time was right to move into Pennsylvania, where supplies were more plentiful than in war-weary Virginia. He hoped to humiliate the Union on their own land.

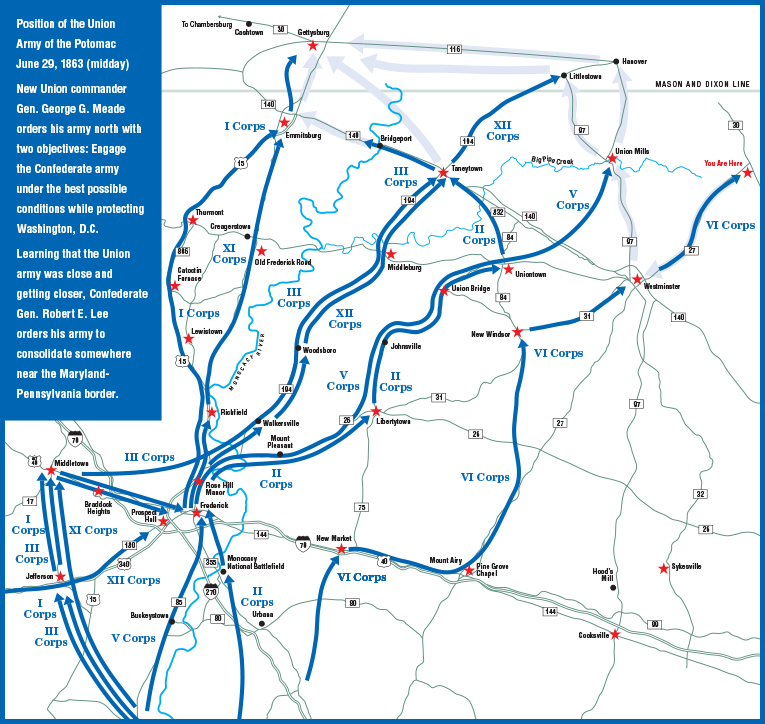

Lee’s army marched north, crossing the Potomac River at Williamsport, MD in mid-June. He kept to the west of South Mountain, shielding his advance from the Union army who was to the east of the mountain range. J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry, however, swung around to the east, crossing into Maryland at Rowser’s Ford in Montgomery County. They proceeded north through Rockville, capturing a wagon train that provided much-needed supplies, but slowed their progress. This delay would impact the battle of Gettysburg in a critical way.

Union General Joseph Hooker also turned his troops north, and they crossed the Potomac into Maryland June 25-27 at Edwards Ferry, also in Montgomery County. Nearly 75,000 troops marched through Poolesville on their way to Frederick. By now, Confederate troops were spread out south of Chambersburg, PA. Because Stuart detoured, neglecting his intelligence-gathering role, Lee was in the dark about the Union’s location.

Early the morning of June 28, George Meade was camped on the grounds of Prospect Hall in Frederick when he learned President Lincoln had appointed him general of the Army of the Potomac, replacing Hooker. Meade’s immediate priority became protecting Baltimore and Washington from a Confederate attack; therefore, he ordered Union troops north on every available road.

Citizens of the small Maryland towns between Frederick and the Pennsylvania line were about to witness the Union army trek past their doors.

Marching North

Route 15 To Emmitsburg

I started at Prospect Hall (889 Butterfly Lane), where Meade assumed command, a home I have driven past many times without knowing its significance. The mansion, which would have been considered very grand for Frederick in the time period, still stands. I then headed north on present-day Route 15, which the First Corps also traveled on June 29 in a chain of 15,000 men, 2,900 horses and mules, and 475 wagons. The trek they made on that rainy day from Frederick to Emmitsburg was 18 miles, past Lewistown, Catoctin Furnace, and Thurmont.

Since my journey that day was Civil War focused, I didn’t spend time at Catoctin Furnace, one of my favorite historic sites in Frederick County, but I recommend you do. The museum is currently closed due to the pandemic; however, guests can see the old furnace, the quaint worker houses, and the ruins of the Ironmaster’s Mansion, and then take a hiking trail overpass to Cunningham Falls State Park on the other side of Route 15.

As I explored the Civil War Trails signs in Thurmont, I stumbled upon two covered bridges – Roddy Road and Loys Station. The Maryland Inventory of Historic Places estimates a circa 1860 construction date for both bridges (although Loys Stations’ was rebuilt after a 1991 arson), meaning they stood witness to the columns of northbound troops.

Not far from the Roddy Road bridge is a strategically-placed Civil War Trails sign right beside the tasting room at Catoctin Breeze Vineyard. I had never been to this winery, and it was far too early in the day for me to taste the wares. But with the picnic tables, live music, scenic vineyard, and mountain views, I added it to my bucket list for another day.

I then headed to Emmitsburg. The town, only 10 miles from Gettysburg, served as a staging and fall back area during the battle. Interestingly, Emmitsburg suffered a fire only two weeks before the Civil War arrived at their doorstep. Seeing the scorched ruins on their approach, Union forces believed the Confederates had burned the town. The blaze, which started in a stable and was unrelated to the war, ended up destroying about 40 homes, including three-fourths of the town square. When you visit today, most of the architecture in the center of town is post-1863.

Route 194 To Taneytown

General Meade himself traveled north from Frederick via present-day Route 194 with the Third Corps through Walkersville, Woodsboro, and Middleburg, before locating his headquarters in Taneytown on June 29. Troops were greeted with songs, cheers, and home cooked meals in each town they entered. Soldiers spent the night in Taneytown, camping on the grounds of Antrim 1844, today a hotel and fine dining restaurant. The bell tower of Trinity Lutheran Church was pressed into service as a signal tower, relaying messages between Taneytown and the Lutheran Seminary in Gettysburg.

The army then marched towards Gettysburg through Emmitsburg, receiving sustenance from the Daughters of Charity, who would become battlefield nurses days later. Today, visitors to the Seton Shrine in Emmitsburg can view an exhibit and take a tour detailing the sisters’ role in the Civil War. I did both several years ago and found them very moving.

Route 26 to Union Mills

The Second and Fifth Corps headed north on present-day Route 26 through Libertytown, Uniontown, and Union Mills. I thought I would just drive through Uniontown, not expecting to fall in love with the quaint town. I adore historic homes, and Uniontown has them in spades; the main street still looks much as it did when the troops rolled through 150 years ago. As a result, the town is listed on Maryland’s National Register as an outstanding example of the linear rural towns that were common in north-central Maryland in the nineteenth century. (Here is a walking tour of the town.)

After adding the town to my dream home real estate search engine, I headed to Union Mills Homestead. The army camped on the grounds here before marching northwest to Gettysburg via Littlestown and Hanover. Today, this museum provides a glimpse of nineteenth century rural farm life through living history interpretation. Although the museum wasn’t open during my visit, I spent time wandering the site, taking photographs of the old homes and mill. I’ll definitely go back, hopefully during the Civil War encampment scheduled for July.

Route 27 to Manchester

The Sixth Corps headed north on present-day Route 27, passing through New Market, another historically preserved town on my dream home list. A soldier remembered this town, writing “two or three young ladies were discovered standing in front of their home waving small Union flags. It was an electrifying sight…there was no question now that [we] were in the land of friends.”

Following the Sixth Corps’ route, I visited Pine Grove Chapel in Mount Airy, a preserved stone chapel built in 1846. At this point, I was supplementing my itinerary with the Carroll County Roads to Gettysburg Driving Tour, which pointed me off Route 27 to New Windsor. This area of the state is still very rural, mostly fields with an occasional historic farmhouse and barn dotting the picturesque countryside. As I drove, I reflected on how similar the landscape I was seeing today was to what the Union army witnessed. Indeed, the Civil War Trails sign at New Windsor confirmed for me the beauty made an impact on the soldiers, with one writing “I think it is the prettyist [sic] place I ever saw.”

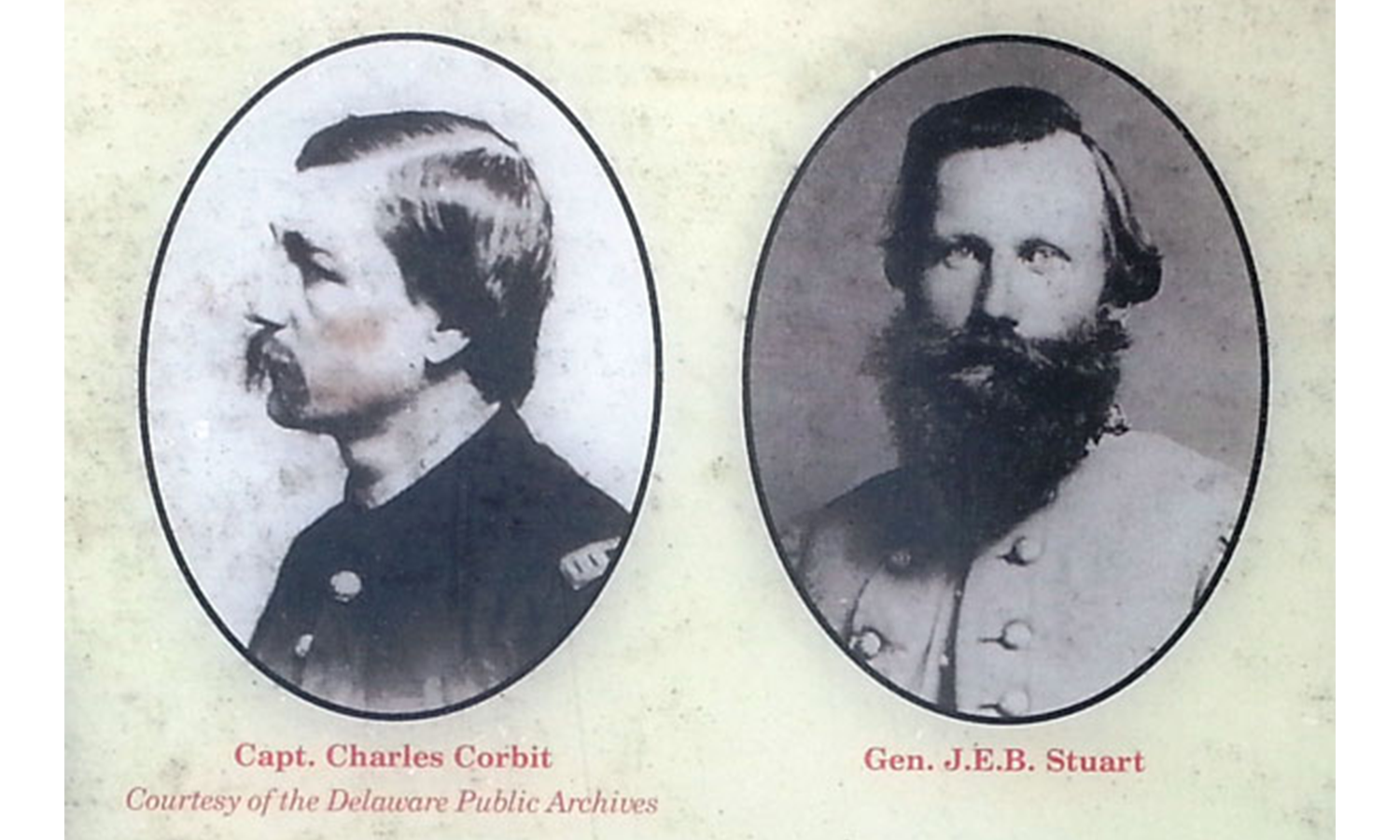

In downtown Westminster, I was reminded of J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, which had been busy requisitioning supplies in Rockville. They caught up to the Union army here, where they skirmished in a conflict known as Corbit’s Charge on June 29. It ended in defeat for the Union; however, it had larger consequences for the battle of Gettysburg. Because of this encounter, Stuart spent the night in Westminster, delaying his arrival at Gettysburg until July 2. Historians still ponder how the battle might have changed if Stuart had arrived on time. (A walking tour of Civil War history in Westminster is here.)

My last stop was Manchester, where Union troops were stationed to guard the roads to Baltimore and Washington. They were joined by the Sixth Corps, who had marched 22 miles from New Windsor in the hot June sun. After a day of rest, they headed out to Gettysburg, traveling another 34 miles and arriving to reinforce the Union lines on the evening of the second day of battle.

After the Battle

I was exhausted, and I had driven the entire thing. I couldn’t imagine marching it, in wool, in the summer heat, with gear, after untold prior miles and battles.

We all know that the battle of Gettysburg lasted three days, July 1-3, 1863, and resulted in a Union victory that turned the tide of the war. Both armies then retreated through the same Maryland towns, which were rapidly filling up with wounded soldiers being treated in makeshift hospitals. Those stories could fill another post.

I have only touched on the tip of the Civil War history that exists in north central Maryland. If you wish to explore further, there are a variety of resources, many of which you can find on the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area website, which covers Washington, Frederick, and Carroll Counties.

Lead Photo: 2016 Union Mills Reenactment. Photo Credit: Union Mills Homestead Foundation

About the Author

Heidi Schlag

Heidi Glatfelter Schlag is a marketer, history lover, and traveler who can often be found exploring museums, parks, small towns, and farms. She foundedCulture-Link Communications, where she helps local nonprofits and small businesses build their brands. Heidi lives in Frederick, MD, with her husband and two dogs.