Follow the Footsteps of an Assassin on the John Wilkes Booth Trail

Americans who had been celebrating the April 9, 1865 surrender of General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate forces were stunned by the April 15 headline screaming from the The New York Times.

“President Lincoln Shot by an Assassin. The Deed Done at Ford’s Theatre Last Night. THE ACT OF A DESPERATE REBEL.”

The leader who had delivered them through the Civil War was dead, and a manhunt was on for the murderer, actor John Wilkes Booth. Rewards totaling $100,000 were being offered for the capture of Booth and his accomplices.

We now know that Booth headed south through Maryland, crossed the Potomac River, and was captured in Virginia. His trip is memorialized with the Civil War Trail’s John Wilkes Booth Trail, which leads you to a series of wayside trail markers, as well as several museums and other locations that Booth passed during his escape.

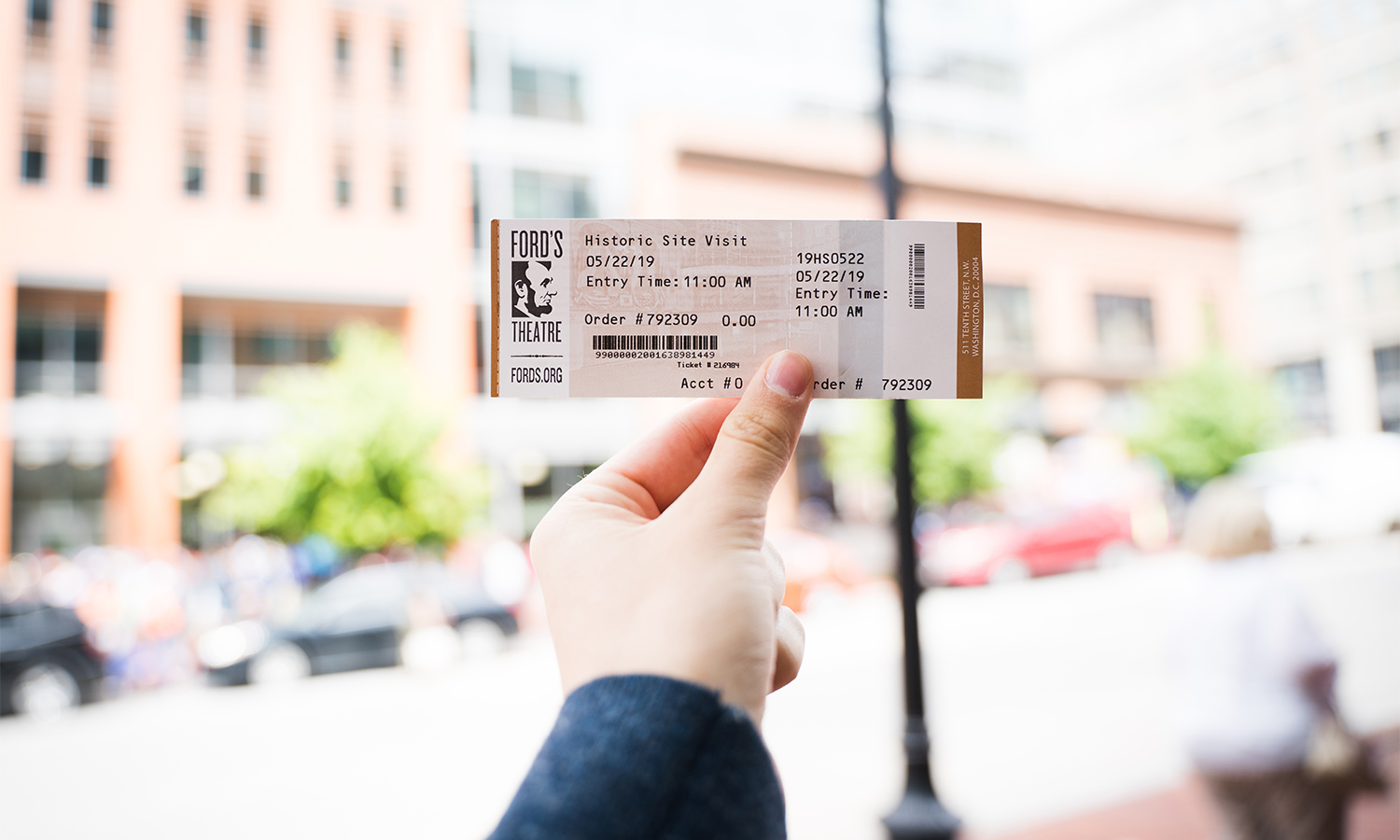

Ford’s Theatre

Of course, the crime itself occurred at Washington D.C.’s Ford’s Theatre, during a showing of the comedy Our American Cousin. After shooting the President, Booth leaped from the Presidential Box to the stage below, breaking his leg. This injury would have implications for Booth as he made his escape.

Today, you can catch a show at Ford’s Theatre, explore the museum exhibits documenting the event, and visit the home where President Lincoln died.

The Theatre also offers a walking tour with re-enactor-turned-detective James McDevitt that examines clues at eight locations the real McDevitt investigated the night of April 14, 1865.

While you are in the District, seek out some hidden history with ties to Booth: the Wok and Roll restaurant at 604 H St NW in Chinatown. This building was once the Mary Surratt Boarding House, where Booth met with his conspirators and likely planned his crime. A plaque marks the home today.

To learn more about Booth and his conspirators, my husband Joe and I headed to southern Maryland to visit two homes Booth stopped at during his escape, now both museums.

Surratt House Museum

We started at the Surratt House Museum in Clinton, MD. The red two-story home sits at the crossroads of what were once the main north-south and east-west routes through the area, originally called Surrattsville for John Surratt, who operated a small tobacco plantation, tavern, and post office in the structure. John was dead by the time his wife, Mary, and his son, John Jr., made the acquaintance of Booth.

About 90 minutes after shooting the President, Booth and his accomplice David Herold rode up to the Surratt house on horseback. They were there to pick up field glasses, a bottle of whiskey, and two carbines (repeating rifles), supplied by Mary and John, Jr. Within seven minutes, the felons had their supplies and were back on the road.

During our tour with our knowledgeable guide Catherine, we learned that, due to Booth’s broken leg, he wasn’t able to carry a gun while riding a horse. This left the tavern keeper with an extra carbine, which he stashed in the wall between the kitchen and dining room. This wall was later ripped apart by investigators, and the hidden rifle was used as evidence against Mary Surratt. She was charged with conspiracy to assassinate President Lincoln, convicted, and hung, becoming the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government.

We enjoyed seeing the house, which was furnished with period pieces and painted historically accurate colors, thanks to painstaking paint analyses. Besides discussing the plot to kill Lincoln, the tour covered the functioning of a tavern during the time period and the slaves that kept the plantation and tavern running. After the tour, we spent about 30 minutes reading the exhibit panels in the museum, which provided an in-depth look at the state of the nation before and after the assassination.

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House Museum

Next, we traveled about 30 minutes south to Waldorf, MD’s Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House Museum, a telescoping white farmhouse still surrounded by acres of farmland. There, we were met by our costumed guide Susan. She showed us the two-story home, which was more upscale than the Surratt house. Because the Mudd home had remained in the family for generations, most of the museum’s furnishings could be traced to either to Dr. and Mrs. Mudd themselves, or close relatives.

Booth had met Dr. Mudd in 1864, ostensibly to buy land, although more likely because Booth was aware of Mudd’s political leanings. Historians suspect Booth had enlisted Mudd in his plans because of his medical knowledge—he was a well-respected physician. Whether Mudd knew Booth was planning to murder the President is up for debate; the original plan was to kidnap Lincoln, and it is unclear whether Mudd had been informed that the plot had shifted to murder.

Regardless, Booth and Herold arrived at the Mudd house around 4 a.m. on April 15 so the doctor could treat Booth’s broken leg. We saw the very sofa and bed that Booth rested on; it was very surreal to be steps away from furniture with such a nefarious legacy.

Again, the details of what happened next are murky. We know that Booth and Herold rested at the Mudd farm, and that they escaped before the police arrived, following a tip that Mudd was acquainted with the pair. It is apparent that the Mudds did not share the news of their visitors in a timely manner, thereby leading to Dr. Mudd’s arrest and conviction for conspiracy and harboring felons. He was sentenced to life in prison, but did not hang, as the other conspirators did.

Our tour ended in the back of the house, where a dirt road winds into the distance. We learned that this is the road Booth and Herold escaped on, leading them farther south. There hasn’t been any development around that road; you can picture the two fugitives galloping off, running for their lives.

The Rest of the John Wilkes Booth Trail

After the Mudd house tour, Joe and I headed home. As much as we wanted to continue, we had dogs waiting at home for their supper. One day, we will return south to complete the Trail, as I am told that the Samuel Cox home is being restored and developed as a museum. Booth and Herold stopped at this Bel Alton, MD, residence, also known as Rich Hill, on April 17.

On April 21, the two felons crossed the Potomac River, leading the chase into Virginia. Their luck ran out on April 26 at the Richard Garrett farm south of Port Royal, VA. They were found hiding in a tobacco barn; Herold surrendered, but Booth refused. Trapped in a burning barn— the fire was set by the troops to flush him out—Booth was shot and pulled from the flames. He died a short time later. The Garrett farm no longer stands, but there is a Civil War Trails wayside sign near the location.

Lead Photo: Aidan Green via Shutterstock.com

About the Author

Heidi Schlag

Heidi Glatfelter Schlag is a marketer, history lover, and traveler who can often be found exploring museums, parks, small towns, and farms. She foundedCulture-Link Communications, where she helps local nonprofits and small businesses build their brands. Heidi lives in Frederick, MD, with her husband and two dogs.