Major Leaguers for Miles in the Free State

As many baseball-loving Marylanders know, Babe Ruth was born in Baltimore (at 216 Emory Street, to be specific). He was deemed “incorrigible or vicious” at age 7 and sent to Saint Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, where he learned to play the game of baseball with the encouragement of one of the school’s priests, Brother Matthias. With prodigious power at the plate, an appetite for the limelight, and a life of excess, Ruth became a national icon, and his name is still revered in the sport he began playing professionally more than a century ago.

The state’s contributions to professional baseball go well beyond the Great Bambino, however. Eight other players from Maryland have been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and dozens more contributed to the game and helped it grow.

With the boys of summer completing a most unusual season last month, I set out on a recent weekend to visit the hometowns of five Maryland-born ballplayers to learn about their humble beginnings and paths to major league greatness.

Frank “Home Run” Baker – Trappe, MD

Before Ruth burst on the scene, the king of the round-tripper was John Franklin Baker, a third baseman who played with the Philadelphia Athletics in the early 20th century and, later, the New York Yankees. Baker’s power earned him the simply stated sobriquet “Home Run.” He led the American League in long balls for four straight seasons, from 1911 to 1914, but never hit more than 12 in that span, thanks to the dead ball of the era.

Baker was born, lived, and died in Trappe, a rural town on the Eastern Shore between Easton and Cambridge. In the 1890s, when Baker was growing up on his family farm, baseball was huge on the shore, and it was common for towns and companies to field their own teams.

After retiring as a player, Baker settled back into life in his hometown, managing as many as five farms at one point and serving for a time on the town board and as director of the State Bank of Trappe. A visit to Trappe shows traces of his time here are still intact. His house at 3872 Main Street still stands, and the bank branch is now home to a cafe, The Coffee Trappe. The town has a park named after Baker with two little league fields and a paved walking path. There’s also an informational plaque about the ballplayer’s career and contributions to the town.

It wasn’t until 1955 that Baker was selected by the Veterans Committee to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame. He died eight years later and is buried at Spring Hill Cemetery in Easton. The tombstone includes an etched stained glass window with flowers, a bat, glove, and baseball near its base.

Also in the Area: Stop at Momma Maria’s for Mediterranean cuisine and craft cocktails, or take the short drive to Cambridge for beers at RaR Brewing.

Jimmie Foxx – Sudlersville, MD

Shortly after his retirement, Baker was tapped in 1924 to manage the newly created Easton Farmers in the Class D Eastern Shore League. He heard of the exploits of Foxx, a farm boy and star athlete in Sudlersville, about 35 miles northeast, and invited him for a tryout.

Before he even finished high school, Foxx had an offer to play for the Philadelphia Athletics and left home in 1925 to take part in spring training. During stints with the A’s and Boston Red Sox, Foxx became one of the greatest right-handed batters of his era, hitting .325 with 534 home runs and 1,922 RBI. He’s one of only 11 players to win three or more MVP awards.

Driving into Sudlersville off U.S. 301, visitors can turn right from Route 300 onto Dell Foxx Road, named for Jimmie’s father. On the left, they’ll see part of the farmland where Jimmie was born, and on the right, they’ll see the farm he bought his parents, who were tenant farmers when he became a successful pro ballplayer.

In town, the high school where Foxx excelled in baseball, soccer, and track still stands, at 300 S. Church St. (only now it’s the elementary school with several more modern expansions in the rear of the brick building).

Both the Sudlersville Train Station Museum and Sudlersville Memorial Library have exhibits on Foxx, which include old pictures, memorabilia, photos, and other items. At the center of town, near Sudlersville’s one traffic light, is a statue of Foxx in his A’s uniform, bat held behind his head as he finishes the follow-through on his mighty swing. A nearby plaque outlines the many feats of Foxx’s career.

Also in the Area: Grab a few drinks at Patriot Acres Farm Brewery just north of town or visit historic Dudley’s Chapel.

Bill “Swish” Nicholson – Chestertown, MD

One of the preeminent power hitters of the World War II era, Bill Nicholson was a part of the 1945 Chicago Cubs team that won the National League pennant and, infamously, drew the ire of a spectator after he and his billy goat were ejected from Game 4 of the World Series.

The outfielder finished his career as a part-time player with the Philadelphia Phillies, reaching the World Series again in 1950 with the “Whiz Kids,” so nicknamed because the average age on the roster was just over 26.

Nicholson spent most of his life near Chestertown, and like Foxx and Baker, he grew up working the family farm, helping milk cows, and grow fruits and vegetables. If you drive out of Chestertown on Route 20 and turn right onto Earl Nicholson Road, you can immediately see some of the acres they worked.

Following his baseball career, he went back to farming, living out the rest of his days on a 125-acre spread near Langford Bay, outside Chestertown. In 1992, a statue of Nicholson — dressed in his Cubs uniform and finishing the follow-through of his swing — was placed between the town hall and the visitor’s center. The plaque at the statue’s base notes the tribute to a “great man” and said the memorial serves “as a reminder that sport is an important part of the American Dream.”

Nicholson died four years later and was buried at St. Paul Episcopal Church.

Also in the area: Drink cocktails and distilled spirits at BAD Alfred’s Distilling, enjoy a meal on the water at 98 Cannon Riverfront Grille, or check out the stores, restaurants, and galleries in Chestertown’s historic downtown.

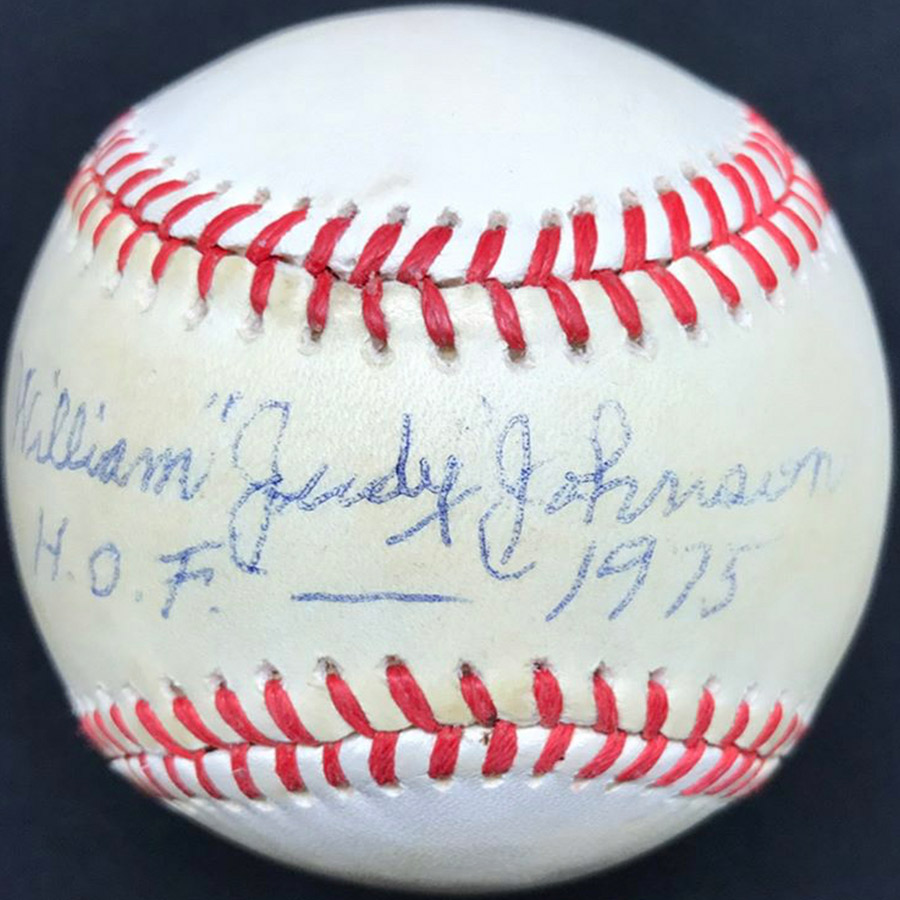

William “Judy” Johnson – Snow Hill, MD

Born around the turn of the century, Johnson grew up and played at the height of segregation in the United States, with African-American players not allowed on major league fields until 1947. Instead, players of color joined their own teams, and the first of several formal leagues was started in 1920. After playing semi-pro ball in his teens, Johnson starred on the Hilldale Daisies — located in Darby, Pennsylvania outside Philadelphia — in the 1920s, and later played on the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords.

The Negro League Baseball Museum notes that Johnson was “an all-around great third baseman” and smart base-runner despite his lack of speed.

“A right-handed line-drive hitter with an excellent batting eye, he hit for good average but not with exceptional power,” the museum says.

Following the integration of baseball, Johnson worked as a scout for the Philadelphia Athletics, Milwaukee Braves, and Philadelphia Phillies. His longest tenure was with the Phillies, where he worked from 1959 to 1974 and served as a coach during spring training.

In 1971, he joined the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Committee on the Negro Baseball Leagues to pick players deserving of enshrinement. Four years later, Johnson stepped down from the committee and was picked to enter the hall, becoming the sixth Negro League player to receive the honor.

Johnson was born in Snow Hill, a charming small town on the Pocomoke River and the seat of Worcester County. At the age of 5 or 6, Johnson and his family moved to Wilmington, Delaware, where his father worked in the shipyards. Johnson’s father wanted his son to become a boxer, but “Judy” later recalled that he “couldn’t fight a lick.”

Last year, the town installed a monument dedicated to its native son and “one of the greatest third basemen” of all time outside the local branch of the Worcester County Library, on N. Washington Street.

Also in the area: Learn about history and folk art at the Julia A. Purnell Museum or take to the water with a rental from the Pocomoke River Canoe Co.

Robert “Lefty” Grove – Lonaconing, MD

One of Jimmie Foxx’s teammates and friends in both Philadelphia and Boston was Robert “Lefty” Grove, a southpaw pitcher and winner of 300 games. A fireballer in the early part of his career who later developed a full repertoire of pitches, Grove is considered one of the greatest left-handed pitchers of all time — some would argue the greatest pitcher, period, given his accomplishments during the offensive explosion of the 1920s and 1930s.

Grove spent almost his entire life in Lonaconing, a small mining town in the Georges Creek Valley area of mountainous Western Maryland. Like a lot of young men, he left school early to help work the mines. But the job didn’t suit him.

He began pitching for a semi-pro team in nearby Midland and quickly worked his way up to the minor league Baltimore Orioles, where he pitched for five seasons. Philadelphia acquired the southpaw in a record-setting deal, and after a rough rookie season, Grove won 13 games with a 2.51 ERA in 1926 and never looked back.

At the height of his career, Grove opened a bowling alley and pool hall, known as Lefty’s Place, in his hometown. There was candy on sale for local kids and a trove of memorabilia from his storied career, including more than 200 baseballs from the games he pitched.

Following his death in 1975, Grove was buried in Frostburg Memorial Park, about eight miles from Lonaconing. A small memorial, on which admirers have placed hats from Orioles, Athletics, and Red Sox, sits several feet in front of the headstone.

Lefty Grove Park, just off Main Street in Lonaconing, features a gate modeled after an entrance at Oriole Park at Camden Yards and a bronze statue of Grove on a pitcher’s mound, delivering one of his electric fastballs. Plaques placed throughout the park tell the story of Grove’s roots, his professional career, and the mark he left on his hometown.

Just down the block, at the George’s Creek Library, Grove’s 1931 MVP trophy and other artifacts are on permanent display.

Also in the Area: Explore the 19th-century Lonaconing Iron Furnace and surrounding park, or head up to Frostburg’s historic downtown.

Lead Photo: Brandon Weigel

About the Author

Brandon Weigel

Brandon Weigel is a writer and editor based in Baltimore. His work has appeared in Baltimore Fishbowl, City Paper, The Washington Post, and other outlets. When not traveling the state, you're likely to find him enjoying a good whiskey, watching the Orioles and Ravens, or driving his beloved vintage Mercedes.