The National Museum of Civil War Medicine: Connecting Bloody Battles to Modern Medical Care

“It’s not real,” I had to remind myself as I leaned in to inspect the mannequin of a dead Civil War soldier. His face was gray, as if all of his blood had been drained by the faux embalming surgeon standing over him. The scene is one of many captivating exhibits at Frederick’s National Museum of Civil War Medicine, an institution highlighting the war’s medical breakthroughs and how they relate to the present.

The museum’s exhibits are broken down into the roles medical practitioners played in the soldier experience, from recruitment to death. Visitors can’t help but feel an emotional response from the life-sized dioramas.

In addition to the haunting embalming scene, I sensed the pain of the wounded private as he received first aid in the Field Dressing Station scene and the tender care recuperating soldiers received in the Pavilion Hospital scene.

The museum’s most famous artifact is the Antietam Arm, a mummified limb supposedly found on its namesake battlefield. As I stared at the straggly appendage, I thought about how frightened the young owner of this arm must have felt to go into battle with the knowledge of what could happen to him.

The museum seeks to dispel common myths about Civil War medical practices. For example, it’s a misnomer that surgeons, nicknamed “Old Sawbones” by soldiers, were unqualified and performed amputations because they didn’t know any other treatments. In fact, most surgeons went to medical school or trained with a doctor, and they performed so many amputations because they didn’t have a better option to stave off infection against the destructive effects of the war’s powerful weaponry. And a soldier who underwent amputation rarely bit down on a bullet to channel the pain. According to the museum, 95 percent of men received anesthesia, usually chloroform or ether. The mantra is repeated so often in the interpretive text that I expected to find it printed on T-shirts for sale in the gift shop.

U.S. Army medical wagon behind surgeon with surgical assistant administering anesthesia.

My ticket into the museum included the “One Vast Hospital” walking tour of downtown Frederick. I visited on a temperate Saturday, and the city had a festive atmosphere as shoppers and diners crowded the tree-shaded sidewalks. The tour focused on a less joyous period in the city’s past when about 10,000 injured soldiers joined Frederick’s 8,000 residents in the aftermath of the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam in September 1862. As we walked through the city’s historic core, tour guide Michael Mahr pointed out churches and public buildings that served as makeshift hospitals. Of the 27 buildings called into service, nearly half still stand.

One of the surviving buildings is Visitation Academy. I gazed at the East Church Street complex as Mahr read an account from a wartime seminarian who wrote about the heartbreaking wails emitted by the hurt soldiers. Another citizen described Market Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, as caked in blood. I’ll think about that next time I grumble about a pothole.

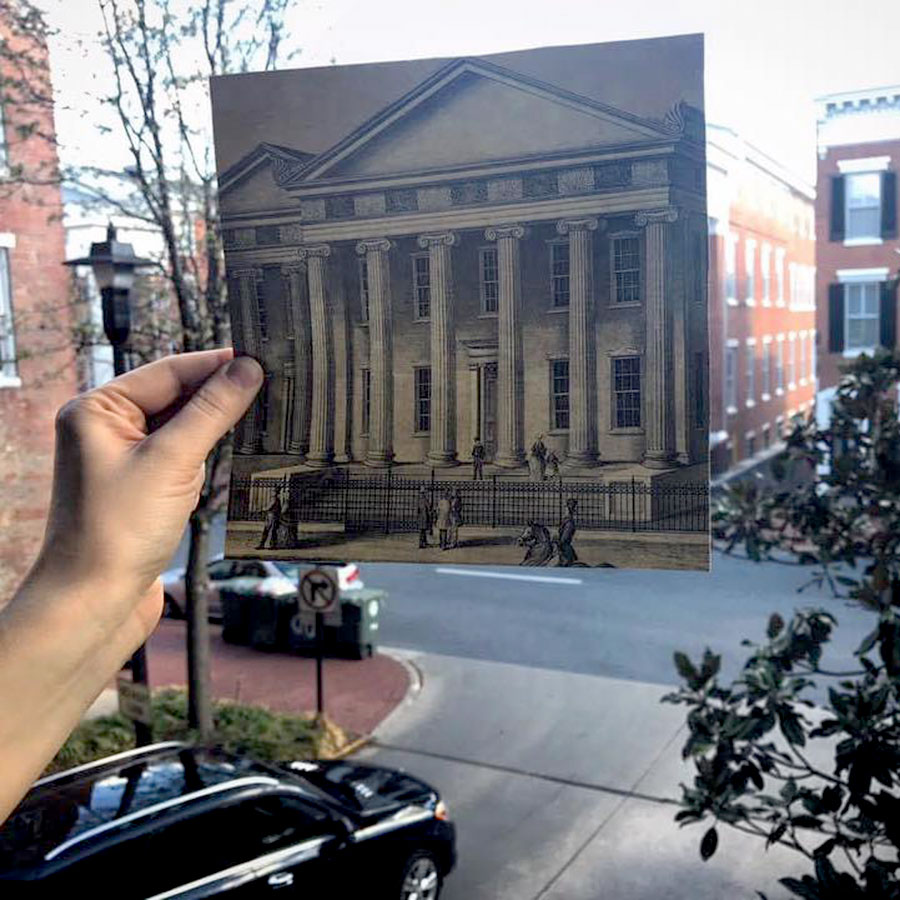

Winchester Hall in Frederick, MD, served as a Civil War hospital. At the time, the building served as the Frederick Female Seminary; it now serves as Frederick County government offices.

But the tour was not all negative. Mahr also discussed the revolutionary evacuation system developed by the Army of the Potomac’s Medical Director, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, regarded as the Father of Battlefield Medicine.

Early in the Civil War, removing the wounded from a battlefield was haphazard and could take many days. Letterman organized a system in August 1862 in which trained stretcher bearers quickly evacuated the injured from the lines for more efficient triage process. Those who had a chance to survive were shuttled to a field hospital for further treatment. Soldiers who needed a long recuperation were sent to more permanent hospitals.

Letterman’s system was so successful that the foundation is still in practice today—both in combat medicine and emergency medical services. “A lot of what EMTs do involves the Letterman system: treat the immediate injuries first, load them into the ambulance, and take them to the hospital,” Mahr said.

A couple of weeks later, I drove to Keedysville to tour the Pry House Field Hospital Museum near the Antietam National Battlefield (about 20 miles west of Frederick). Owned by the National Park Service, the two-acre property is operated by the museum as a satellite location. (The organization also runs the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office in Washington, D.C.)

I turned off Shepherdstown Pike and headed down a driveway toward the Pry House, perched on a hill like a jewel on top of a crown. Built in 1844, Philip and Elizabeth Pry lived in this distinguished brick home with their five children on September 15, 1862, when they received a fateful visit from a Union officer. Soon, thousands of Union soldiers descended on the farm, and the Army of the Potomac established its headquarters there.

I understood why the Army wanted to commandeer this farmstead while struggling to carry my infant daughter up the steep lawn. The bluff above Antietam Creek affords good views of the surrounding countryside. The U.S. Signal Corps set up a signal station here to communicate with the lines and relay information to other stations via flags and torches. Major General George B. McClellan, who led Union forces during the battle, watched part of the fight from here. And, most importantly to the museum, the Pry House was the medical headquarters for Letterman and his team as they carried out his new system. The Battle of Antietam is referred to as the bloodiest day in American history and had approximately 23,000 casualties, including 17,000 wounded. Hundreds of those injured fighters were transported to the field hospital on the property.

As I perused the interpretive panels in the Pry House’s sitting rooms, one of my fellow visitors entered the parlor on the opposite side of the ground floor. “I thought I was in here by myself and walked in here and jumped!” she said. She had stumbled upon a scene that showed Union Major General Joseph Hooker sprawled on a dislodged door as Letterman tended to the gunshot wound on his foot. A bloody boot lay on the floor. Hooker recovered from the injury and went on to assume command of the Army of the Potomac a few months later.

A scene at the Pry House shows Dr. Letterman treating Maj. Gen. Hooker.

Major General Israel Richardson, the man depicted in an upstairs bedroom, did not have such a favorable outcome. Known as “Fighting Dick,” he was struck in the chest by a shell fragment and whisked to the Pry House to recover. (President Abraham Lincoln visited him here.) Richardson succumbed to his injuries many weeks later and died in the room where you’ll now find a bedridden mannequin representing his final days.

The battle changed the trajectory of the Prys’ life. “It would’ve been very chaotic when they got back,” said Rachel Moses, the Pry House site manager. Union soldiers had helped themselves to the family’s livestock; impaired soldiers were crammed into the barn, and officers were laid up in the house. Philip Pry received some compensation from the federal government, but the family was financially ruined and relocated to Tennessee in 1874.

After I left the house, I stopped in the side yard to examine the medicinal herb garden. The dozens of plants grown there were used during the Civil War and included herbs such as St. John’s wort, which has been used for millennia to treat depression and anxiety. I was surprised to see hops in the raised-bed garden, but I later read on the museum’s website that it was grown to represent the popularity of beer in Army life.

Stepping into the barn at the base of the hill, I felt as though I had entered a church. Sunlight seeped in through the planks that enclosed the cavernous space, and the only sound I could hear was the chorus of crickets in the soybean fields just outside. I looked up at the original timber frame that ascended toward the ceiling, the same view a wounded soldier would have had as he rested. Most of the floorboards have been replaced since then, but the wider and smoother wood pieces toward the barn’s south end dated to the battle. A Civil War-era ambulance wagon is on display in the middle of the barn, its boxy shape reflected in the design of today’s emergency vehicles.

A few days later, I was in my car when an ambulance screamed past me on its way to a nearby hospital. I thought of Letterman and his other innovative colleagues, who made the most of awful circumstances to improve medical care for everyone going forward.

If you go

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine is located in Frederick and is open year-round. The Pry House Field Hospital Museum is located in Keedysville and typically is open seasonally. Visit the museum’s events page for the latest information on tours and programs.

Lead Photo: Visit Frederick

About the Author

Chris Berger

Chris Berger works as an urban planner and is fond of Maryland’s historic architecture, nature, and sporting traditions. He lives in Montgomery County with his wife, daughter, and dog. You canfollow him on Instagram @cjberger1.